Creative Thinking in Math Class

Credit: Fair use

I gave a TEDx talk on this topic earlier. I have written and revised the same ideas in essay form.

Most students will say math class is stupid and boring. As a math person myself, I have to say: they’re right! Math taught in school is twelve years of Pavlovian training to associate math with arbitrariness and fear. Not only does this rob the student of a potentially enjoyable experience, it robs the student of the transferable skills that are exercised in math. I will give two examples.

Transferable Skill: Problem-Solving

Asking novel kinds of questions teaches students how to solve problems they haven’t explicitly learned how to solve. In any job position, you will be asked to do this. Some students are afraid to trust their own original thoughts. Explicit practice with feedback can help them eventually use their own intelligence when making choices. I don’t think only asking novel questions to students is necessarily a good idea, but I think we to ask more than none.

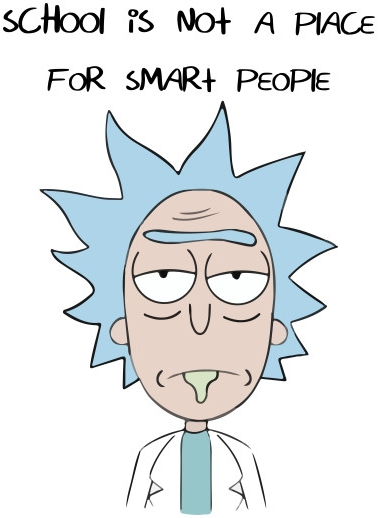

Here is a problem that requires original thinking to solve the first time.

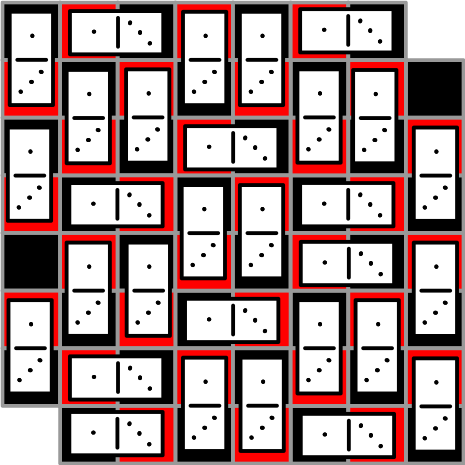

This is a checkerboard with dominoes where each domino takes up two squares.

It can be tiled with dominoes without any overlap or dominoes hanging off of the edge.

If I cut off the two opposite red corners, can I still tile the board?

You may identify one tiling pattern that does not work, but can you convince me that no tiling pattern will work?

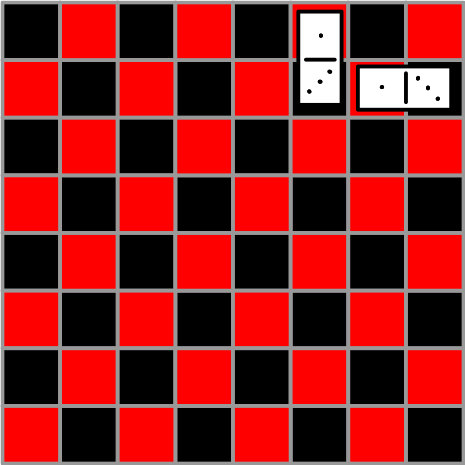

This is a tough question, but in cases like this, a teacher can ask leading questions that guide the student to an answer for the difficult question. For example, the teacher could ask,

- How many squares are there on the original board?

Think before clicking

Since the board is 8x8, there were 64 squares before the two corner tiles were removed. - After the corners are removed, how many of those that remain are

black? How many are red?

Think before clicking

Out of the original 64, there must be 32 red and 32 black, but I cut off two red squares. Therefore there are 30 red and 32 black. - Can I place a domino such that it covers only two black

squares?

Think before clicking

No. Each domino must cover one red and one black, no matter how it is placed. - Back to the original question, can all of the red tiles and all of

the black tiles be covered by dominoes?

Think before clicking

No, because the are 32 black tiles, 30 red tiles, and each domino must cover one of both. No matter how you do it, you will end up with 2 uncovered black tiles.

Paradoxically, the teacher helped the student by asking more questions. Students do not even need a grasp of math before they can begin answering novel questions like this one.

This style of thinking is valuable without a mentor as well. Students should learn that even though they can’t answer the big question, they can still make up other small questions (using some of their own ingenuity) which they can answer. Perhaps math units should start with guiding questions, and then slowly allow the student to make up their own questions. Currently, there is absolutely no incentive for students to think of their own questions about the concepts they are learning.

Transferable Skill: Communication: Explaining and Persuading

The method of teaching used above is called the “Socratic method.” Socrates famously explained mathematics to an uneducated servant. Explaining complicated things in simple terms is an art. There is not necessarily a ‘right’ way of explaining something, but some ways are better than others.

Currently math curriculum does not even attempt to challenge students’ ability to explain and persuade. Students go on to their future studies and jobs lacking the ability to explain something technical to people who don’t already understand it and to convince people of something they don’t already believe. These are both skills that could be exercised in the context of math.

Here is an example. When I was in middle school, I was arguing with my friends about whether 0.999… (repeating forever) was equal to 1. I thought it was not the same as 1, but a hair less than 1. My friend Ben was just as adamant that 0.999… exactly equal to 1. His explanation was short, but persuasive.

- He asked us if we believed 1/3 = 0.333… exactly, no approximation (if you could expand the ellipsis infinitely). We of course agreed.

- Then he asked us if 1 = 3 × 1/3 exactly. Nothing special here either.

- Then he said that 1 = 3 × 1/3 = 3 × 0.333… exactly. “Ok?” we nodded.

- When multiplying decimal digits, you multiply each digit by the multiplier, so 3 × 0.333… = 0.999… exactly. We learned that years ago and used it recently.

- Hence 1 = 3 × (1/3) = 3 × 0.333… = 0.999… exactly. It’s just another way of writing the same thing.

Here is an entertaining presentation of this and similar arguments.

We were reluctant that there was more than one way of writing a number in decimals—namely 1 and 0.999…—but logic has no such hesitation. Once you go looking, you can find more examples of numbers with multiple decimal names: 0 is 0 or -0, 4 is 4.00 or 4.0.

If you are still not convinced, you have to reject one of the individual steps, but each step is exceedingly reasonable—even obvious—in isolation. That’s what makes this argument so cogent. At each step, he thought from our perspective: “what facts does my audience already believe and how can I use those?”

Although he knew more math and jargon than us, he deliberately did not use it because he wanted us to understand it. People with an overinflated ego argue or ‘explain’ using complicated topics that “you wouldn’t understand”; people of true intelligence argue or explain something complicated using simple terms, see Richard Feynman.

Perhaps randomly assigned groups of students could present each concept to the rest of the class. They would have to prepare a lesson and field whatever questions or confusions the rest of the class had. Aside: one of my classes did this. It was illuminating to see the differences in how other people understood and learned the concepts. Talking out competing viewpoints exposed a lot of misconceptions, sometimes even in the student-teachers. Without that experience, those misconceptions might never have been noticed and corrected. What’s more, in these discussions, it was explained exactly why the misconceptions are wrong, and not just “because it is” or, worse, “because the teacher said so.”

Perhaps classes should also incorporate proof-writing into their class. Most math competitions (like USAMO and Putnam) do this and have efficient infrastructure for grading. Students should be graded on mathematical correctness and “elegance.” I understand that it would take more teacher-effort to grade these essay-like responses, but I hope you see why I think that’s a good trade. While elegance can be subjective, it is not more so than grading essays in English class. I think the skill of explaining is inherently subjectively evaluated in any form, but by no means should that complaint excuse us from practicing a vital skill.

Making Things Better

I don’t know exactly how to incorporate these ideas. Surely there is some value and wisdom in the traditional system; everyone needs to learn fractions. I am merely pointing out that maybe we need some traditional rote-learning mixed with novel problem-solving and communication, which are currently absent completely. In English class, where there is time allocated to appreciate the great masters and to express your own ideas creatively. I think math can be studied more like English If not for the sheer beauty of mathematics or blissful joy of creativity, then for the pragmatism of transferable skills students could gain in the process.

Twelve years of seemingly ceaseless mental drudgery extinguish any remaining ember of mathematical creativity, curiosity, or inspiration from students (see the wonderful A Mathematicians Lament by Paul Lockhart for more in this vein). It’s no wonder most students hate math; I couldn’t do a better job of making people hate it if I tried! It’s also no wonder that sometimes people at their job act like mindless drones with no ability to improvise or innovate in a self-motivated way.

I won’t pretend I am the first person on earth to notice this (see Math Teachers Should Be More Like Football Coaches). These ideas are already implemented in some institutions. I was lucky enough to have dedicated teachers who went above and beyond what was required to implement these ideas. They also believed in me, and I am grateful for that. I hope to follow their example with my own spin on things too.

Math is Art

From the Mayans to the Greeks, from Babylon to the Indus River, every civilization has developed the disciplines of music, painting, and math. It satisfies some basic human desire to explore the unknown, express ideas, and awe at sheer beauty. Sometimes it happens to be useful, but its purpose is to be beautiful.

That’s what math actually is to those who practice it. You get to make crazy up hypotheticals (e.g. “what if we had numbers whose squares are negative?”) and investigate them to their logical conclusion (e.g. complex analysis). There are many more of these: “are all infinities equal?” gives cardinal and ordinal numbers, “could a computer program prove everything?” gives computability theory and the incompleteness theorem.

I have found many practical reasons to teach math differently, but this is the one that resonates with me the most: math is a creative pursuit, and keeping this a secret among math people prevents a lot of people from experiencing the sublime, stupid-giddy, joy of being creative in this way.